Nov 20, 2025

Articles

The Voice at Risk: What AI cannot learn for us

Why the apprenticeship of writing matters, and why outsourcing it to machines imperils the very voice it is meant to form.

Haley Moller

CEO

“The subterranean miner that works in us all, how can one tell whither leads his shaft by the ever shifting, muffled sound of his pick? Who does not feel the irresistible arm drag? What skiff in tow of a seventy-four can stand still? For one, I gave myself up to the abandonment of the time and the place; but while yet all a-rush to encounter the whale, could see naught in that brute but the deadliest ill.”

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, Chapter 41

Every apprenticeship in language is begun in darkness. A child learning to speak does not consult a grammar book—she listens and imitates; her tongue fumbles through sounds that make no sense, and only after months of this unsteady improvisation does she begin to utter anything that might be called a word. Writing is much the same. Its growth is subterranean: a long, slow accretion of habits gathered from other people’s sentences, from a teacher’s red ink, and from the silent, unbidden music that steals upon us in books, shaping the ear long before the mind perceives the structure of such music.

It might seem that learning to write well comes about by sheer determination; yet, as Melville reminds us in the above quotation, whatever proves deepest in us is nurtured in hidden places, beyond the reach of conscious striving. Writing skill emerges the way fluency in a new language does—not by memorizing rules, but by steeping oneself in the living practice. Good writing is the residue of thousands of small acts: composing a sentence and erasing it, reading a chapter and feeling some shapeless part of oneself shift in response, and imitating a passage so closely that its structure becomes your own without your knowing it. To write well is to have been worked upon by that inward miner whose strokes we scarcely hear, and whose unseen borrowings shape our voice long before we ourselves know its name.

This quiet apprenticeship used to happen almost without our noticing. Students wrote because they had to, and in the ordinary friction of trying to say something, they rubbed off their clumsy habits and discovered better ones. They read because it was assigned, and in reading absorbed the rhythms of fine writing. Even the dread of a teacher’s corrections, however painful, helped anchor certain instincts. Over time, these small currents converged into something unique and sturdy: a voice.

But we are living through a moment when that slow, essential process is in danger of being quietly undone. Among the many threats attributed to artificial intelligence (job loss, misinformation, overreliance on machines), the most intimate and least remarked is the eclipse of writing as a lived practice. When I spoke with a high‑school teacher recently, she admitted that almost none of her students write anything on their own anymore, not even emails. They open ChatGPT before they open their mouths. A simple message to a teacher—“Here’s the assignment; sorry it’s late”—is now drafted for them. Students are not cheating, exactly; they are afraid of sounding wrong and afraid that their unpolished voice might reveal too much of its inexperience, youth, and partialness. And so they pass over the very stumbling through which a voice is born.

Completing writing assignments with AI is like trying to learn French in Paris with an ever‑available personal translator. Having a translator would be immediately gratifying—you could make yourself perfectly understood; and in addition, you wouldn’t have to deal with that insufferable Parisian snobbery (any American who has tried to practice French in Paris will know what I mean), but your French would remain stagnant, because language is acquired not just through exposure but through allowing yourself to make mistakes, misunderstand, and stumble toward meaning as a baby does. Linguistic fluency is not the sum of perfectly translated exchanges; it is the accumulated sediment of imperfect ones.

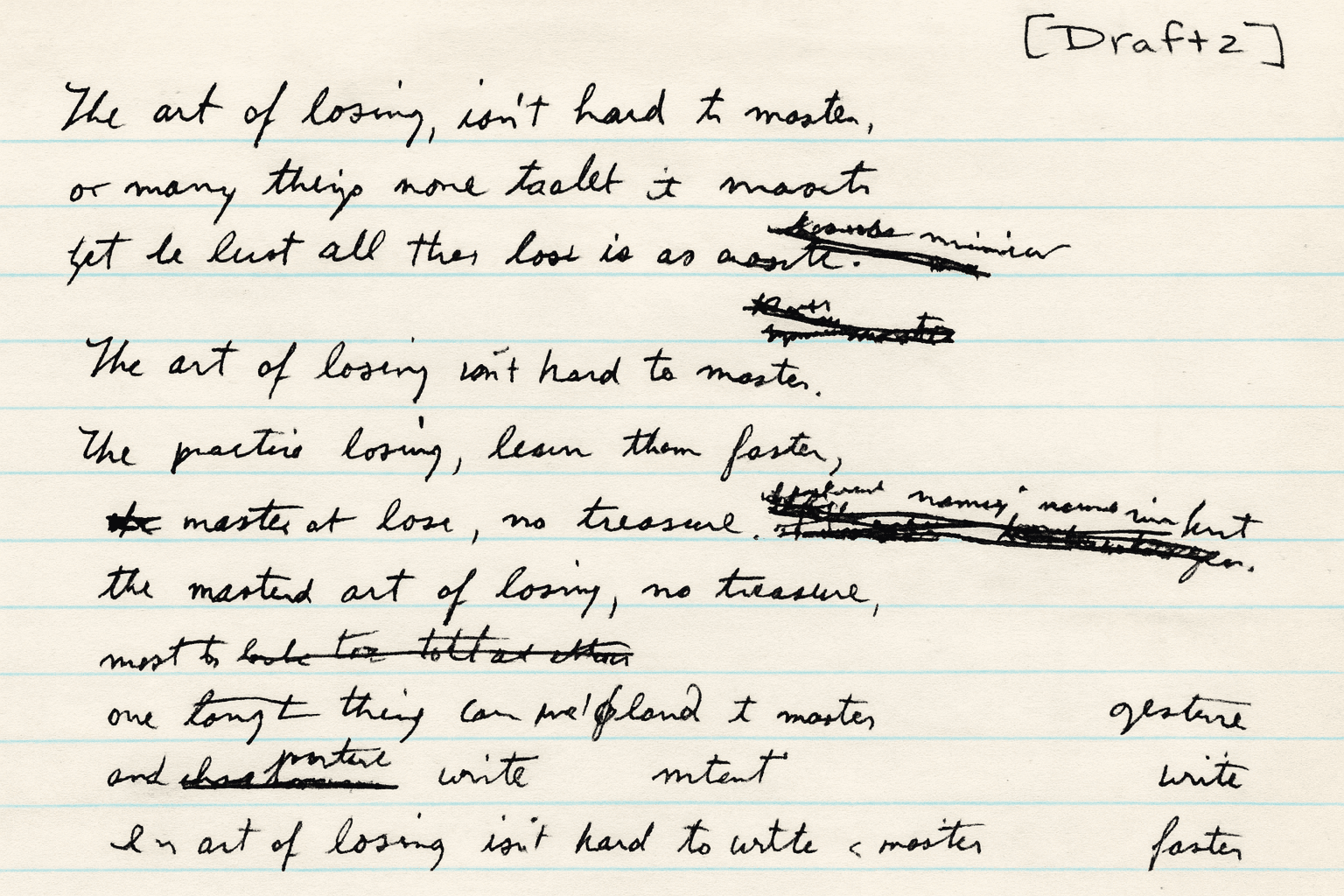

Writing is no different. Acquiring the skill depends on the brain’s ability to map thoughts to words through effort, hesitation, and revision. And this inscrutable process cannot take place if an algorithm performs the work for us. Indeed, the very delicacy that makes writing difficult is what makes it transformative. When a student strives to give her meaning shape, striking out a metaphor that jars upon her sense or painstakingly refashioning a sentence that will not carry its thought, she is schooling her mind into finer precision. Writing clarifies thought because it forces us to confront its incompletions. It is not certainty that prompts us to write, but the hope that, in writing, the uncertain may find its shape.

This inner work has no immediate spectacle. No one applauds the tenth revision of a single paragraph, or the small click of understanding when a student finally untangles the logic of her own argument. These moments are invisible, like the faint stirrings by which a buried seed splits open and reaches for air. But millions of such moments accumulate into the capacity we call “a writer.” And if those moments are replaced by a system that produces sentences instantly, the internal work never happens.

Every technological advance asks us to decide what part of ourselves we are willing to delegate. We have long delegated navigation to GPS and arithmetic to calculators. But delegating writing is different, because writing is not merely the transcription of knowledge; it is the mechanism by which we develop a voice. If we outsource this, we risk outsourcing not just the words but the very personality and thinking behind them.

What will become of a generation that never experiences the clumsy earnestness of early prose? What happens when students skip the phase of being “bad writers,” which is as necessary to becoming a good writer as childhood is to adulthood? Our fear of sounding unformed may cost us the chance to form at all.

And yet, I do not believe the future is foreclosed. As George Eliot remarked, “Every ending carries its own beginning.” There is still time to stand beside students and say: your voice matters more because it is imperfect. That awkward early draft, the one you are ashamed to turn in—that is the rough seed of something only you can grow. There is no shortcut around it, only through it.

The most important question is not whether AI will change writing—it will—but whether we will stop young people from skipping the humble, taxing apprenticeship through which writers have always emerged. We stand at a threshold much like those early hosts of new technologies, wondering whether convenience will eclipse craft. But writing, like language itself, is a human inheritance older than any tool we have built. Its sources lie in the slow, private act of finding words for one’s own experience, and in the knowledge, faint but steady, that expression is a kind of faith.